It is a known fact that the role of NGO’s in inclusive education goes beyond the skill of reading and writing. It opens our mind to the world and empowers us to independent. Currently we live in a world where education is considered to be a basic right for all. But not so long ago, it was a luxury for many.

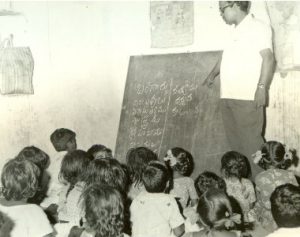

In 1978 the Education sector was founded by RDT with the goal to ensure the enrollment of children from disadvantaged communities. At that time, 90% of them were not even attending primary school. RDT began conducting awareness sessions with the parents and simultaneously supplementary schools were started.

In the 80s, the organisation’s main focus was on curbing school dropouts and gradually people from disadvantaged communities began to access higher education. Wale Naik, Ramakrishna and Adilakshmi are all part of the first generation of children supported by RDT’s education program.

Wale Naik’s parents were illiterate. The incentive of receiving a supplementary meal was his main motivation for joining the RDT school in his village. Theresa, one of the first teachers at the RDT schools says, “No one really knew what it meant to have an education. Most of the parents worked in the fields from dawn to dusk for a meagre daily wage. Some kids came to school untidy and unkempt. The first thing of the day was to give them a bath.”

But for Wale Naik his most precious memory of those days is of the kabaddi, an indigenous contact sport, and volleyball competitions organised at the school. “I was well known in my village for my performance during kabaddi competitions. I received many awards.” For the first time in his life, he could enjoy participating in activities with other students his age without caring of which community or family he came from. Today, Wale Naik works as a teacher in a government school and through his work ensures that every child has a happy and safe childhood like he did.

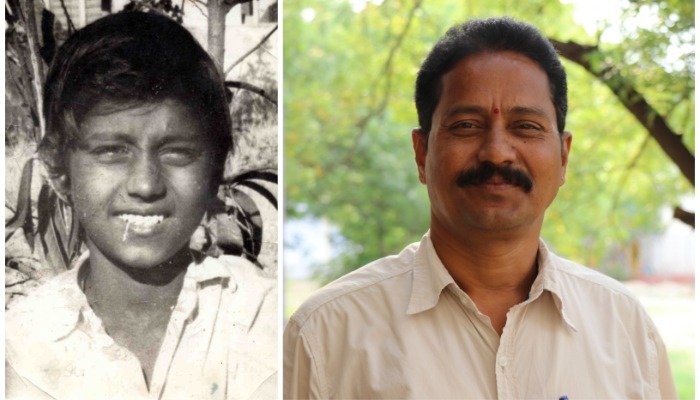

Ramakrishna went to the RDT supplementary school since he was seven years old. It was 1978 and unlike the schools he attended in the past, the classes were taught in English instead of Telugu and students took part in many fun activities. And most importantly, “we were all the same,” he explains.

“We used to learn songs and dances and play sports.” His engagement in sports and cultural activities built his self-esteem and confidence. “In the school I got the knowledge to succeed in life and through sports and cultural festivals I got the recognition of my family and community for the first time.” Currently he is working as a technician in information and broadcasting in Hindupur. He still treasures the first Telugu-English dictionary that he bought in the first year of university with the support of the RDT Scholarship.

For Adilakshmi, RDT supplementary school was not just a place to learn but also a safe haven where she could be herself. Her parents were farmers in her native village of Pinaigeripalli and were against sending her to school for education. “My father used to take me out of the school and make me work in the fields. It was very tiring while at school I was learning to read and write. I used to cry a lot,” she remembers. “According to him girls were supposed to work on the fields and get married but I persisted to pursue my education through the support of my brother. On the day I received my first university degree, he aplologised to me and we hugged,” she recollects.

Adilakshmi became the first woman in her region to have a university degree. Today she has four Master’s degrees and is the main librarian of the Anantapur District Library. Through her work she encourages the youth to study so they can pave their way towards a bright and independent future.

RDT’s exceptional role as an NGO working for education guarantees sustained access to education for all at all levels are ongoing. The continuous programmes and activities over the years have made it possible to achieve 100% enrolment at the primary level in all the villages that RDT works in.