This article was previously published by YouthKiAwaaz

“Do you want us to close the door?”

“No, better not. The neighbours might suspect and they will eavesdrop.”

We are in a small house in the silk district of Hindupur, a city situated on the border of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The house has only one room and a single bed, which Lakshmi* (38) and Narasimha* (42) share with their two children, Preeti* (15) and Praveen* (18). Four buckets and a closet are the only elements that stand out in the room. The family sustain themselves by producing silk threads.

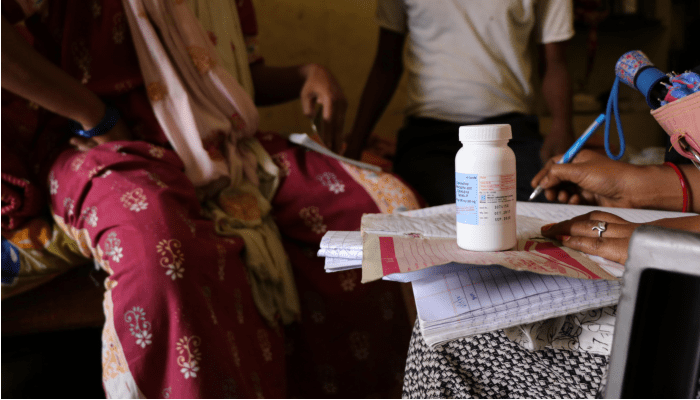

It is 11 AM. Lakshmi and her husband are waiting for Lalitha Kumar*, the outreach worker of Rural Development Trust (RDT), who visits them monthly since she and her husband were diagnosed with HIV. The goal of outreach workers like Lalitha is to ensure adherence to medication, check the health status and resolve queries, as well as provide moral and emotional support.

Not just governments, but community-based organisations play a crucial role in addressing the social and economic consequences of a virus that affects 37,9 million people worldwide.

According to the National Aids Control Organisation (NACO), over 21 lakh people were estimated to be living with HIV in 2017, of which Andhra Pradesh ranks second. This is the state that RDT mainly works in, an NGO that runs a Hospital for Infectious Diseases (HID). This centre provides free first and second-line antiretroviral treatment, after being recognised as an ART+ Center, by the Andhra Pradesh State Aids Control Society (APSACS), NACO and it is one of the referral centres for HIV/AIDS and TB in Andhra Pradesh.

RDT’s applies a holistic approach regarding HIV/AIDS, by not only providing medical treatment but also at the grassroots through a network of social and outreach workers. Working from within the communities has been proved to be, in India and worldwide, one of the most effective ways to improve the adherence to treatment and tackle the stigma still associated with it.

Lalitha Kumar has been following up with the family since they reached RDT Hospital a few years ago. She was the first person with HIV that Lakshmi encountered and the only one, besides her doctor, with whom she can talk freely, share her fears and doubts. “Before my diagnosis, I did not know anything about the disease. I heard about it in the TV but I never thought it could happen to me”, Lakshmi she adds while fidgeting with the ARV medicine bottle.

Although there has been a decline in recent years, almost 27% of the total AIDS-related deaths in India occurred in Andhra Pradesh or Telangana, according to NACO’s India HIV Estimations 2017 report. Sex with non-regular partners, especially in men, low condom use, trafficking of girls and women, frequent migration and a large number population of truck drivers are some of the factors that explain the high prevalence rate of HIV in both Telugu states

A sudden silence falls in the room when Preeti, the youngest daughter of the couple, enters the house. She is unaware of her parents “problem”, as Lakshmi calls it. When she leaves, we resume our conversation. Sudden silences, whispers, keywords and hidden medicines have been part of their daily lives for years.

However, their eldest son, already 18, knows about the situation of his parents. He paid a heavy price. He had to stop studying when he was 16 in order to support the family, at the time when his father was diagnosed with HIV and tuberculosis. Lakshmi was taking care of him in the hospital. At that time, she still did not know that she had also acquired the virus.

The impact of HIV/AIDS goes beyond health as it has social and economic consequences, specifically for poor and marginalised groups. Frequent medical visits affect the economically backward, especially those who depend on daily wages to survive. HIV therapy is provided for free in government institutions but they can have side effects, and the lack of proper nutrition and the cost of travelling to the clinics can drastically destabilise their already fragile economic situation.

When the neighbours or the head of the silk workshop, where Lakshmi and her husband work 12 hours a day, ask them why they go to the doctor so often, the answer is always the same: “My husband has TB.” HIV is a forbidden word. “They would throw us out of the house, the village and work. It would be our end”, says Lakshmi.

Before leaving the neighbourhood, we accompany Lalitha to visit some other families. They are what she calls ‘cover visits’ so that nobody suspects, nobody knows the purpose of her visits. “A lack of discretion can ruin their life,” says Mina. “Secrecy, lies, deception are the other side effects of this disease and these are rarely treated,” she adds.

This is where the work of community-based organisations become pivotal. Outreach workers and counsellors like Lalitha, help people living with HIV, not only access good-quality health care, but also to ensure the HIV stigma does not spoil their lives.

“Somebody showed me that HIV does not mean death. I am just trying to do the same,” says Lalitha before we bid goodbye to her.

*These names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.